Life as a 'living mannequin'

WARNING: This story discusses eating disorders that may be distressing for some viewers.

One post, two-hundred followers and a three-year contract. That is how a world of glitz and glamour, toxicity and tokenism began for this Australian model. Like many in an increasingly digitalised age, she was scouted via Instagram to consider modelling. This seemingly suspicious message turned into a legitimate job offer:

“I never, ever thought I would be a model. But they signed me straight away. I was sixteen.”

Now represented by Chadwick Models casting agency, Annie Rose Gittany has been photographed by high-end brands like Meshki, AJE Athletica and Vogue Australia.

She says the industry isn’t as glamorous as it seems.

During Gittany’s first two years of work, she was categorised as “In Development”, a time where new models can work for exceedingly low wages and chalk it up to exposure.

“When I was younger, I felt a lot of pressure…to go and build up my name, take on every single job and casting. I modelled for free, or really low rates.”

This is a common reality, with the Australian Academy of Modelling reporting the average age for female high-end models is between fourteen to twenty-five. Gittany says “Male models are older…the youngest a male model will likely be signed is twenty.”

While Australia’s modelling industry are mostly teenagers, models are not protected by child safety laws. Agencies do not employ models as young as fourteen, instead, independently contract them – a loophole in the legislation.

SDA model’s union provides industry and legal advice for exploited models. They believe “young workers are…most likely to be underpaid…by their employer, because they don’t know what their rights are."

As a teenager, Gittany was shocked that “you’re a living mannequin.” Backstage at runway shows, models are stripped naked “in front of so many people all the time.” They don’t know who’s taking photos. Who’s looking.

That’s why all employers who work with minors must legally be authorised by the NSW Children’s Guardian, updated weekly. An examination of the most recent registry approved only six mainstream fashion labels and no modelling agencies. When contacted, Chadwick were unable to comment.

Gittany models for Chadwick models (Chadwick: Jeremy Choh)

Gittany models for Chadwick models (Chadwick: Jeremy Choh)

Gittany models for MINKPINK Campaign (Instagram: Annie Rose)

Gittany models for MINKPINK Campaign (Instagram: Annie Rose)

“Even models pay will come months later. I did a job back in April that I haven’t gotten paid for…sometimes it never comes. It’s common…happens to all models.”

Gittany works four jobs - model slash waitress slash retail worker slash sports coach – while studying Design at university, just to support herself.

She goes on to reveal this is just the beginning.

Within the industry, “a lot of models won’t eat breakfast [before a shoot]. It’s not that every model has an eating disorder. It’s a mental thing.”

There’s an expectation to be “perfect twenty-four-seven. I know one girl who left modelling and is in a mental hospital now, because the experiences she had were so traumatising.”

Over the past year, eating disorder services experienced a 300% increase in demand, with Mission Australia indicating over one-third of youth and 44.3% of Indigenous women were highly concerned about body image. Research by psychology lecturer; Dr. Veya Seekis emphasises the socio-cultural relationship between online influencers and the idealisation of eating and appearance disorders.

While Australia’s modelling industry is rebranding to focus on innovation - Gittany believes diversity in mainstream fashion features performative representation. Multiculturalism is simply “a trend.”

“You only see White and Black models. You don’t see Brown…and that is why I can’t grow in” this industry.

“I’m the only Lebanese model in Sydney. On set, I get called an Amazon woman from people who haven’t seen a lot of culture before.”

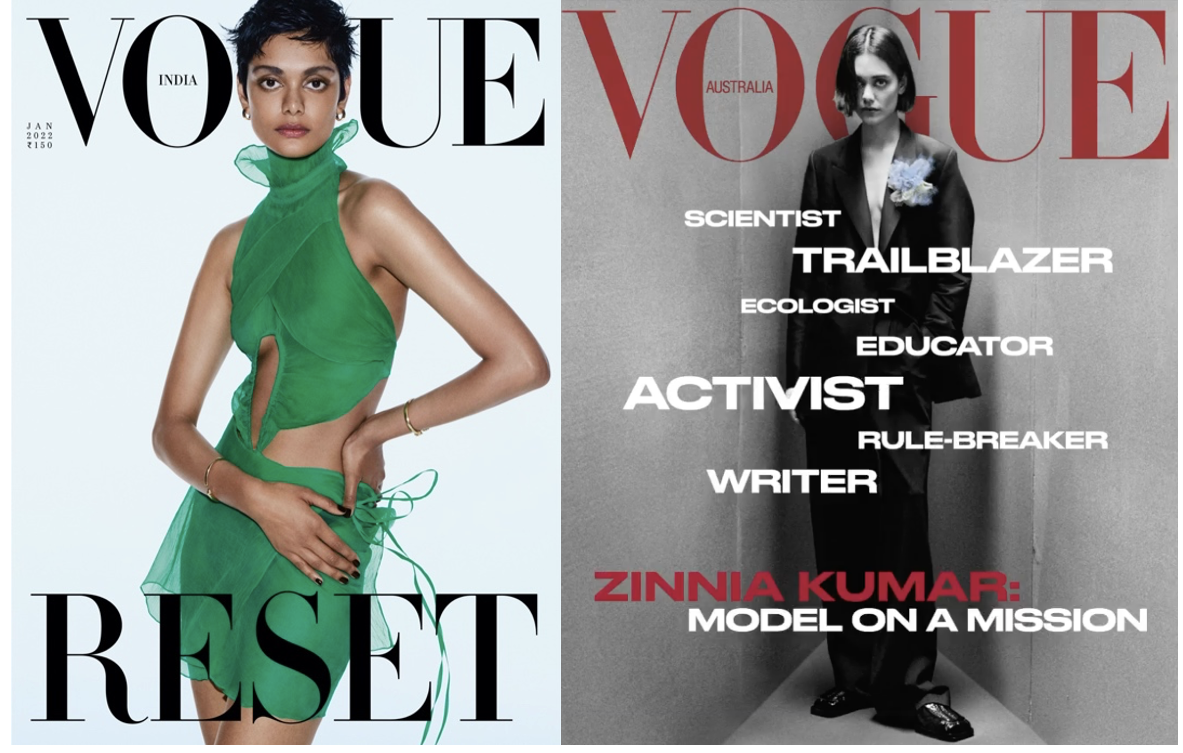

Zinnia Kumar; a colourism advocate, ecologist and international fashion model with a 1.2 million Instagram following, believes diversity isn’t “as straightforward as positive vs tokenistic.”

Kumar has featured on international covers of Vogue and is recognised in Vogue India’s Most Influential Global Indians List 2019:

“The issue with the fashion industry lays behind the scenes…in the C-Suite. New York, London, Milan, Paris and Australia’s [executives] are mostly middle-aged white men. Decision makers do not understand cultural and racial perspective except through their own stereotyped lens.”

Kumar featured on the cover of Vogue India, 2022 (Photographer: Lena C. Emery) and Vogue Australia, 2021 (Website: Zimmia Kumar)

Kumar featured on the cover of Vogue India, 2022 (Photographer: Lena C. Emery) and Vogue Australia, 2021 (Website: Zimmia Kumar)

Despite this, Gittany believes “there’s a big movement towards trying to create a less toxic environment. Younger generation models are a very supportive group of people, who really stick up for each other. Lately, models are rejecting fast fashion…rejecting racism”.

Gittany hopes that consumers will continue to stand up for progress. People think they are influenced by models – “but really, they are influenced by you.”

If you or anyone you know needs help:

- Butterfly Foundation on 1800 33 4673

- National Eating Disorders Collaboration

- Eating Disorders Families Australia

- endED support and information on eating disorders

- Eating Disorders Victoria on 1300 550 236

- Lifeline on 13 11 14

- Beyond Blue on 1300 224 636

- Suicide Call Back Service on 1300 659 467

- Kids Helpline on 1800 551 800

- Headspace on 1800 650 890